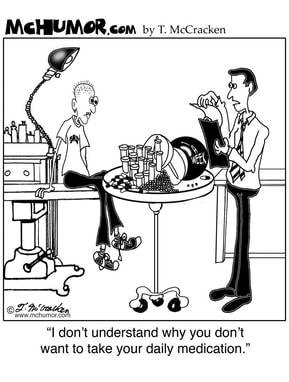

There’s this idea among a frustratingly high number of healthcare providers (HCPs) who take care of teens and young adults that we're “difficult patients” because we don’t listen to their instructions, we don’t take our medications when we are supposed to, we miss our appointments, etc.

I gave a presentation a few weeks ago to a group of HCPs, sharing my personal experiences as a young person with a chronic illness (since living as a cancer survivor is definitely categorized as a chronic illness these days), and talking about ways I thought HCPs could better support young people with chronic illness. I also talked about the importance of teaching young people self-advocacy skills, since navigating the healthcare system can be really tricky without those skills (if you don’t know what self-advocacy skills are, or want to learn more about them, check out my previous post about them HERE).

One of the first questions I got at the end of the presentation was from a doctor who works with AYAs with chronic illness daily. He asked: “When do you think is the optimal time to start teaching self-advocacy skills?” The question made 2 things clear to me: (1) The fact the doctor even had to ask that meant that he doesn’t know if/when to teach his patients these skills and (2) he had probably never asked his patients if they felt prepared/armed with the knowledge/skills they need to navigate their care. He's a great doctor, and does some amazing work, so this really struck me as interesting. The focused attention of the others in the room indicated they probably had the same issues.

Then I thought, it’s no wonder they think we are “difficult.” If we don’t have the skills we need to be engaged in our care - how to communicate, negotiate, seek information, and solve problems, among many other things - we will get overwhelmed by, or not realize the importance of, the many tasks we have to complete to be “good patients.” It's like asking a dog to fetch when you've never taught it how to.

More importantly, things like showing up to appointments on time, taking medicines when we are supposed to, and listening to HCPs instructions are all affected by whatever else is going on in our lives. If I don’t like how a particular chemo pill makes me feel, and I’m never taught what it actually does to help treat my cancer, it starts to look just like the 30 other pills I have to take and I decide, what the heck, nothing’s going to happen if I skip one or two or 3.

If I get too nervous to go back to the clinic because I’m just not ready to get more chemo, or get my test results, and I don’t really feel comfortable telling that to whatever receptionist answers the phone to manage appointments. So, I don’t call and cancel - I just don’t show up.

So much can affect what we do or don’t do as patients and survivors. I could go on about that for days. And we definitely don’t have all of the knowledge or skills we need to be able to do exactly as our HCPs tell us all of the time.

Here’s my BIGGEST piece of advice to anyone just starting out on the cancer treatment or survivorship roller coaster: before you get too far into things with your care, with any HCP, set the record straight with them.

Going back to that doctor's question after my presentation, about when to begin teaching patients self-advocacy skills, I think it’s really up to us to let our HCPs know if and when we are ready to get involved in our care. They don’t want to overwhelm you at the beginning, so they may hesitate to engage you in your care. But if you’re ready for it from the beginning, that’s when you tell them. Otherwise, give yourself time to get acclimated and then decide if and when you want to talk with them about what you want out of your care.

What I wish I had done at the beginning of my treatment was something to the effect of “I probably don’t have all the knowledge and skills I need to stand up for myself whenever I might need to during this process, or to be fully engaged in my care, and I may often rely on my parents because of that, but that doesn't mean I don't want to be involved. My lack of knowledge and skills may also affect how well I do everything I’m supposed to as a patient. So, I want to just ask that you do what you can to walk me through this all so I can be a part of it and learn what I need to learn: provide me with the knowledge I need to know what my treatments will do so I can recognise why each piece is important and do my best to adhere to it. I also need you to take a little extra time to help me develop some skills I will need to manage this all in the long run.”

You may also be in the middle of everything and just have a particular issue with something going on in your care. For example, I wish that in the process of making some more difficult decisions about my treatment, I had said something when I wasn’t happy with a choice that was being made about my treatment/care: “Dr. ____ , I just don’t feel comfortable with this decision and I’m not familiar with/entirely comfortable with negotiating about this medical kind of stuff, since I don’t have as much knowledge as you do about this, but you’re going to have to help me out here because I need to talk this through more so we can come to some kind of conclusion that I’m more comfortable with.” Sometimes we have to walk them through it. As much as I wish they would teach mind-reading in medical school, as far as I know, they haven’t yet.

No matter what stage of the journey you're in, there will be times when you'll have to just say things really clearly and direct your HCPs as to how they can better help you.

And for any HCPs who might read this, I just ask that you reconsider your “difficult patients” and see whether there may be some things you could do to help them do better. As patients, we don’t get any medical training. As AYA patients, we also haven't had much life experience yet. Without any training or much life experience, we get thrown into all this life-altering decision-making, 24-hour-healthcare management, pharmacology insanity. We have to learn it all on the fly and that’s super stressful, often to the point where it might just be easier to run away from it/ignore it. If you don’t have the time or resources to support a patient who needs more from you, maybe someone else does and you could refer your patient to them for that extra support. If the extra support still isn’t enough, then maybe just start by trying not to use the phrase “difficult patient” at all. There's a fantastic article that I think makes this point in a much more eloquent way, and advocates for a shift in attitude about the label of "difficult patients": "Good" Patients and "Difficult" Patients - Rethinking Our Definitions in the New England Journal of Medicine. My favorite sentence is this: "That we sometimes feel besieged or irritated by these advocates speaks to opportunities for improvement in both medical culture and the health care system." In my opinion, this translates similarly for HCPs caring for AYAs: if you feel frustrated by AYAs who aren't doing what they're supposed to, then maybe there is room for improvement in how their care is being given. If there's nothing you can do to help them overcome whatever you felt was making them "difficult", then let's at least step away from this idea of AYAs being difficult patients. Being a young person with a serious illness is difficult. Most of the time we really don't like it and wish we could just be healthy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed