This is also one of the more complex aspects of being a self-advocate because the process of solving a problem involves using information-seeking and communication skills. If you have not read my posts about those sets of skills, I recommend you start with those before reading this post.

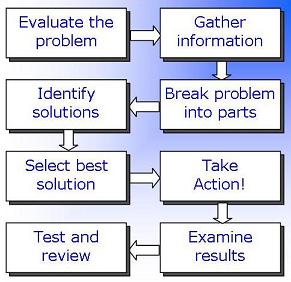

So, to help you become a problem-solver, I will start with this flowchart I found to be really helpful. While this process may seem very detailed, I have found it helpful because it breaks things down into a more manageable process, and enables me to reflect on problems from different perspectives.

- Evaluate the problem.

- Gather information.

- Break problem into parts.

- Identify solutions.

- Select best solution.

- Take action.

- Examine results.

- Test and review.

Let's walk through this process:

- Instead of “evaluate the problem,” I prefer using the words “define the problem,” since I feel it is more clear. So, step one is to define what your problem is. Let’s say, for example, that my problem is that I want to speak up more when I am inpatient (staying overnight in the hospital) and the doctors come into my room on their morning rounds.

- To begin to tackle the problem, start by gathering information. This is where those information-seeking skills come into play. Going back to my example, I would gather information about what doctors I see while I am inpatient and what aspects of my health they are responsible for. I might also brainstorm reasons why I feel I am having trouble communicating with them. When gathering information, I really like to write things down so I can keep my thoughts organized. But, if you prefer other strategies, like talking through things with a friend or family member, you can choose whatever strategy you like. Keep in mind that gathering questions can be part of gathering information. You do not need to have answers at this stage. For example, in gathering information on why I feel I am having trouble communicating with the inpatient doctors, I might come up with questions like “why do they make me feel nervous?” or “why do I feel different about them relative to the doctor I see outpatient”? This step is meant to just flesh out what you know and what you do not know about your problem.

- Now that I have gathered information about my problem, I can start breaking it down. This is a key step I think because, personally, I find that feeling overwhelmed or not knowing where to start can be the biggest barrier to being able to work through a problem. While we have already been breaking things down to some extent, this step really means breaking down the problem you defined. So, going back to my example of of wanting to speak up more to the doctors I see when I am inpatient, I can use the information I gathered to break my problem into parts.

Part 2: What parts of my health are those inpatient doctors responsible for?

Part 3: Why am I uncomfortable communicating with the doctors I see when I am inpatient?

- Let's start thinking about solutions.

If I don not know the answer to this, I can ask those doctors directly, I can ask my nurse, or I can ask my parent/guardian. I can also do some research online to better understand what doctors come on inpatient rounds and what roles they play in caring for patients. From asking people or from researching online, I can learn that the doctors I see when I am inpatient possess a range of skills. I likely will be visited by one attending oncologist, who is in charge of caring for all the patients on the inpatient floor. He/she will possibly bring with him/her an oncology fellow (a doctor who is specializing in oncology and training to become an attending doctor), a few residents (doctors in training - below the fellow in the doctor hierarchy), and maybe also some medical students (students who are studying to become doctors).

Part 2: What parts of my health are those inpatient doctors responsible for?

Again, I can ask people around me about this, or I can take to the internet. In asking around or doing research online, I would learn that the attending doctor is in charge of managing all aspects of my cancer care while I am inpatient. He/she is therefore responsible for all aspects of my health while I am under his/her care. This means that I can ask this doctor any questions, or bring up any concerns - whether they are directly related to my treatment or not. The fellow, residents, or medical students that the attending may bring along on rounds could also answer questions I have, but may be less knowledgeable about the details of my case, and may have less experience, so I should probably direct my questions or concerns to the attending if I have the opportunity.

Part 3: Why am I uncomfortable communicating with the doctors I see when I am inpatient?

This is one I can just think through. I seem to feel uncomfortable communicating with these doctors for a few different reasons. First, when they come into my hospital room, I have trouble understanding who they all are and what their roles are. Second, it is difficult to tell who to ask when I have questions. Third, I feel like they are authority figures and that if they make decisions about my care, they know what is best and I do not need to question it.

- Select the best solution(s). In this example, there isn’t necessarily one “best” solution, so we can also rephrase this step to say select the “best solutions.” From the solutions I previously outlined, I defined who the inpatient doctors are, what aspects of my health they are responsible for, and why I was uncomfortable around them. Now that I have those answers, I can conclude that I don’t need to view them as authority figures because all but one of the doctors that come in are in training, so they are definitely not authority figures. Plus, the attending doctor I see when I am inpatient is responsible for managing my health, but it is MY health, so I can ask any questions or present any concerns to that doctor.

- Take action. Next time I am inpatient and the doctors come in on their rounds, I will better understand their roles and I will be able to acknowledge I have a right to ask any questions or present any concerns. With this new understanding, I will be able to ask questions or present concerns, thereby taking greater ownership of my health.

- Examine the results. If I tried asking questions or bringing up concerns, how did the doctors respond? How did I feel taking ownership in this new way?

- Test and review. If I continue trying to communicate more with these doctors while inpatient, and I feel more and more comfortable doing so, I can tell my problem-solving process has worked. If I do not feel more comfortable doing so, maybe there are more parts to this problem that I need to look into, or other problem-solving steps I need to repeat.

To recap:

Start with defining what your problem is and then gather any information you have about your problem. Gathering information can include brainstorming and coming up with questions related to your problem. Next, break down your problem into smaller, more manageable, pieces. Once your problem is broken down, you are dealing with more specific, smaller issues for which it’s easier to identify solutions. After you have identified solutions to the various pieces of your problem, you can select the best solution(s). Examine the results of your chosen solution(s). Test out your chosen solution(s) and review whether they worked or not. If they worked, great. If not, try going back to your original problem, breaking it down again into more/different parts, and identifying other possible solutions you can try. Whether you like to write things down as you go through these steps, or talk through these steps with someone, problem-solving can take time so be patient with yourself and be open to having to try out multiple different solutions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed